Russia

Ukraine’s energy infrastructure is a major Russian military target. But the system also faces another enemy: climate disasters putting ever more strain on the power grid.

How did the ‘democrats’ understand democracy? On the example of the formation of Moscow’s government

Last year, Alexei Navalny initiated a discussion about the role of the 1990s era in the formation of the modern Russian regime. This debate was eagerly supported by the majority of the Russian left, for whom it became an opportunity to remind once again about the undemocratic nature of the formula of democracy as the power of 'democrats'. Nevertheless, questions about the design of the political system of post-Soviet Russia often remain in the background of this discussion. Alexander Zamyatin shows how the political struggle between the "democrats" and the Mossovet on the eve of the first Moscow mayoral elections in 1991 laid the foundations of the system of power in Russia - from plebiscites to the power vertical.

It often seems that the problem of industrial pollution of the environment is a fairly new phenomenon, which became a topic of wide social discussion only in the second half of the 20th century. Even more novel is the attempt to link environmental problems with issues of state security and protectionist measures. Historian Andrei Vinogradov, using the example of the Waldhof paper mill in Pärnu, shows that more than 120 years ago, issues of exploitation of nature, the imperialist confrontation between the “great powers” and the destruction of the traditional way of life of indigenous peoples were closely intertwined, and environmentalists often had to appeal to “state interests”, to be heard.

Given its powerful oil oligarchs, it’s easy to assume Russia is the quintessential climate denier. Yet the rise of corporate ESG policies in the country suggests Russian capital wants to greenwash just as much as its Western peers.

In July 2023, the international left-wing community was shaken by the news of the imprisonment of Boris Kagarlitsky on the factitious charges of “justifying terrorism”, a code word for his staunch anti-war position. Karaglitsky, the well-known post-Soviet public intellectual, who was previously imprisoned under Brezhnev and Yeltzin, was abducted in Moscow and brought to Syktyvkar, 1,300 kilometers to the north of Russia’s capital. The aim was to isolate Kagarlitsky and cut him off support of his comrades. However, a strong international solidarity campaign led to the sociologist’s release back in December. Now, with his case reopened, Kagarlitsky who refuses to leave Russia as a matter of principle faces five years in prison. September Collective publishes this letter, which Boris wrote from behind bars, to call for reopening of the solidarity campaign for his immediate release with renewed vigor. Freedom to Boris Kagarlitsky and all political prisoners in Russia!

Last August, Alexei Navany published a text, in which he strongly criticised those who, in his opinion, ‘sold, drank, wasted the historic chance which our country had in the early 90s’ - including Boris Yeltsin, ministers of ‘state reform’, and other well-known figures from the post-Soviet Russian elite. This statement, unsurprisingly, led to another round of discussion about the 90s.

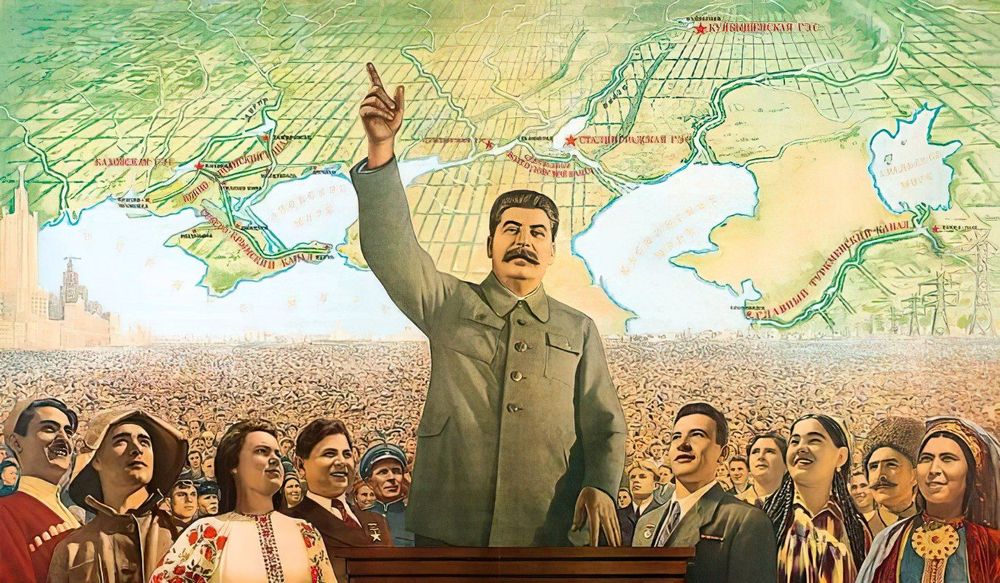

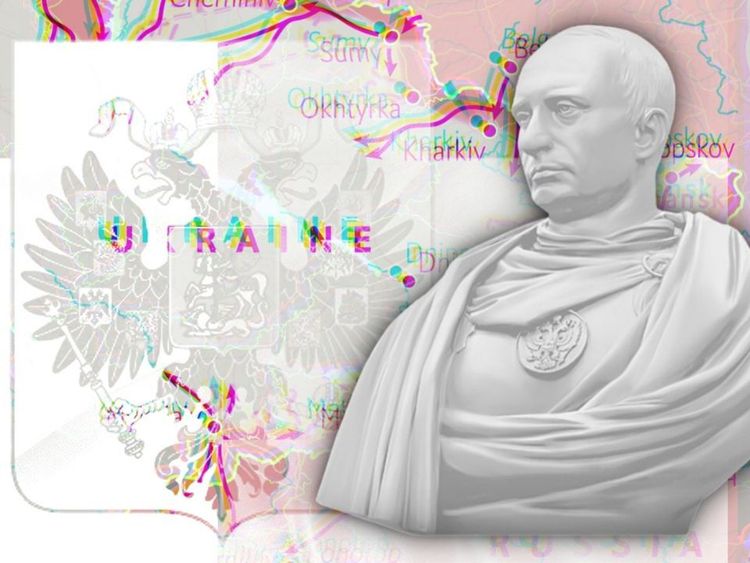

Quite a lot of Russians, including President Vladimir Putin, even though outspoken opponents of the ideas of socialism, nevertheless regard the collapse of the Soviet Union as a personal tragedy. For them, it represented national humiliation for Russia and a chain of major territorial losses. They see in the Soviet project a kind of continuation of, in Putin’s own words, “the thousand-year Russian statehood.” But how did it happen that the revolution that destroyed the Russian Empire, aka the “Prison-house of Nations”, gave rise to a project, certain features of which evoke feelings of nostalgia and revanchism among highly reactionary Russian chauvinists? We publish an excerpt from Marxist historian Vadim Rogovin's book “Stalin's neo-NEP”, in which he describes the transition from the revolutionary deconstruction of the imperial legacy in the early Soviet years to its partial revival in the 1930s. Perhaps it was precisely these changes in the Soviet state that led many to consider it the “same Russia under a different name” and, after its collapse, encouraged the elites of already capitalist Russia to unleash a war to “gather together Russian lands”.

"September" met with mathematician and Russian left-wing politician Mikhail Lobanov to discuss his foreign agent status and his dismissal from the university. We also discussed the potential approaches to anti-war political organizing in Russia and beyond, and learned about Mikhail's plans for the "long-term political mission trip" he embarked on a month ago.

We live in historic times. Historians have long noted that in some periods time seems to thicken, and social contradictions which had previously unfolded gradually are now aggravated and can no longer find room for further coexistence. Current leaders might assure the masses that they are in control of the situation, but if the system goes haywire, this very attempt at mistimed control only worsens the conditions. Gigantic underlying processes are grinding at the superstructural mechanisms, and rulers do not realise the moment that in the long run will make them ex-rulers.

Big business, it seems, is that segment of the Russian elite which has lost most of all in the last year. Russian oligarchs have transformed from yesterday’s welcome guests in London, Monaco or Nice into personae non-grata. Their accounts are emptying, the list of Forbes billionaires is shrinking, and maintaining their usual standard of living is no longer sustainable. However, the ‘revolt of the oligarchs’ expected by many did not happen. We will try to understand how realistic such expectations were, why big business remains an organic part of the Russian political regime without requesting democratisation, and what has changed in its position within the system over the last year.

1991, Leningrad. The private office of the deputy mayor of the city. A reporter for the city's television channel interviews a young official from Anatoly Sobchak's team. In the frame — a man with a childish face in a white shirt. Behind him, you can see window blinds, a television, a table lamp, a telephone, open folders with papers. A typical Soviet office environment. But something does not add up. From behind the scenes, the voice of the journalist says that yesterday, he could still see a bust of Lenin in this office, but today it had disappeared somewhere. What had happened?

It appears that in recent days Russia has been labeled ‘neoliberal’ with increasing frequency. At the very least, this is surprising for the country, where the degree of the state’s involvement in the economy is as significant as it is in Russia and where the president publicly criticizes “neoliberalism.” Is it fair to discuss Russian neoliberalism? In our new text, we attempt to explore why the mainstream approach to the Russian political dynamics is often remote from reality (as, for instance, in the case of the view that the current President subjected “the oligarchs” to his own interests and deprived them of ability to influence politics), whereas the theoretical framework of neoliberalism can explain much about today’s Russia.

A recent post about Kyrgyzstan on Instagram by the popular Russian blogger Ilya Varlamov brought a wave of accusations of imperialism upon him. In this critique, the emphasis was on the boorish way the blogger expressed these statements, while the ideological form of Varlamov’s argument, the concept of a ‘service country’ went almost unnoticed. Let us puzzle out what is wrong with this concept and why it gives rise to such ridiculous statements.

Alexander Korchagin, a student activist, spoke to activists from several universities and told us about the current state of student anti-war activism in Russia.

September met with a municipal deputy of Moscow’s Zyuzino district and an author of For Democracy: Local Politics Against Depoliticization, Alexandr Zamyatin to discuss the reasons to take part in local elections in times of war, depoliticization in Russian and Western societies, and how to overcome it, VyDvizhenie — a support platform for independent candidates Zamyatin founded together with Mikhail Lobanov, — and on the recent transformations of Russian political regime.