Publications for tag «Imperialism»

For several years now, the Georgian protests have been attracting international attention. From March 2023 to the end of 2024, people took to the streets every day, despite police violence and criminal prosecution. Georgians opposed laws modeled on Russian legislation, challenged the re-election of the ruling Georgian Dream party, and protested against the rejection of European integration. Journalist Sasha Fokina spoke with Georgian left-wing activists, who described the state of civil society after the protests.

Ukraine’s energy infrastructure is a major Russian military target. But the system also faces another enemy: climate disasters putting ever more strain on the power grid.

As capitalism-driven polycrisis unravels, Africa disproportionately suffers from the harm brought by climate change. The World Meteorological Organization recognises that temperature increases in Africa are slightly above the global average, leading to growing climate change costs. Meanwhile, extreme weather events across the region, including multi-year droughts and floods, create millions of refugees, although international agencies dedicated to the issue do not estimate current numbers. Despite the fact that this group is the most vulnerable among those affected by climate change, the international regime does not recognise these individuals as refugees, trapping people between existential threats from the climate and asylum bureaucracy.

It often seems that the problem of industrial pollution of the environment is a fairly new phenomenon, which became a topic of wide social discussion only in the second half of the 20th century. Even more novel is the attempt to link environmental problems with issues of state security and protectionist measures. Historian Andrei Vinogradov, using the example of the Waldhof paper mill in Pärnu, shows that more than 120 years ago, issues of exploitation of nature, the imperialist confrontation between the “great powers” and the destruction of the traditional way of life of indigenous peoples were closely intertwined, and environmentalists often had to appeal to “state interests”, to be heard.

September sat down with Quinn Slobodian, author of Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism and Crack-Up Capitalism: Market Radicals and the Dream of a World Without Democracy to discuss his books, the history of neoliberal and libertarian ideas in the 20th and 21st centuries, the war in Ukraine and the current state of the left-wing movement.

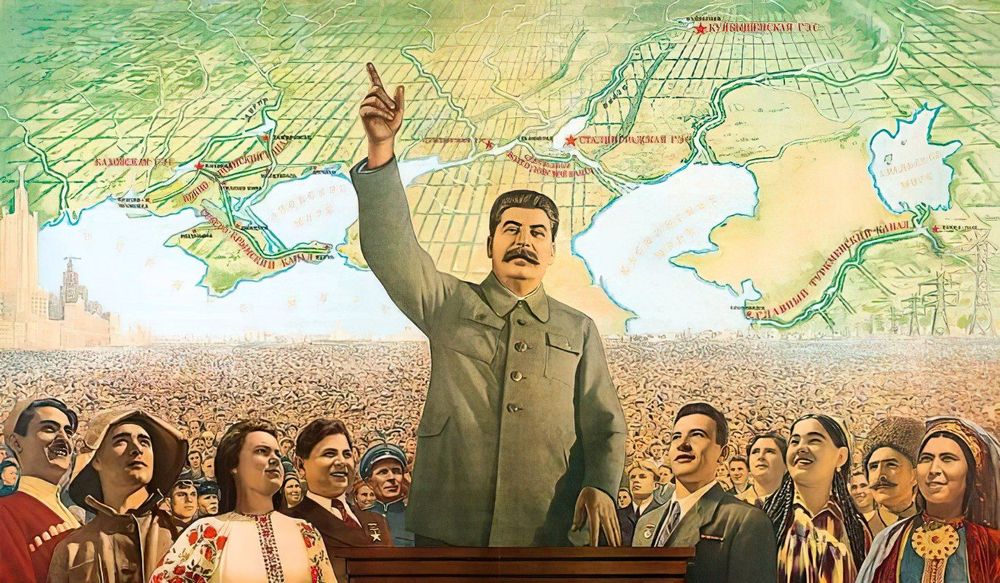

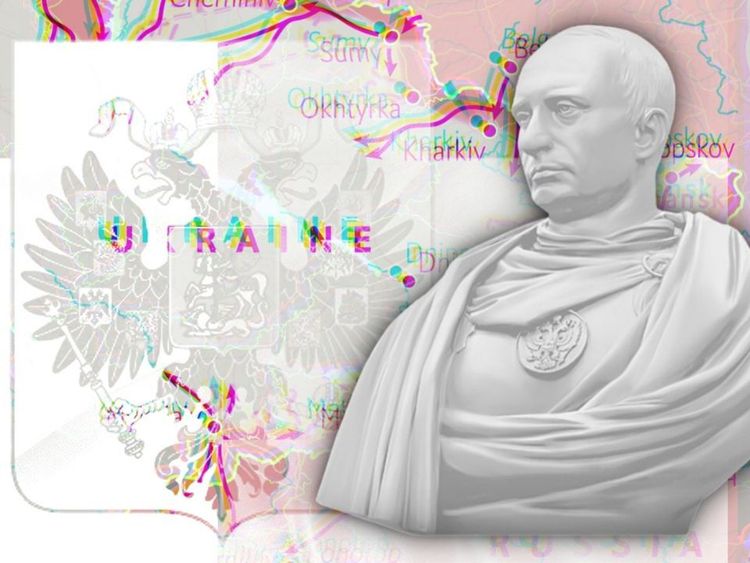

Quite a lot of Russians, including President Vladimir Putin, even though outspoken opponents of the ideas of socialism, nevertheless regard the collapse of the Soviet Union as a personal tragedy. For them, it represented national humiliation for Russia and a chain of major territorial losses. They see in the Soviet project a kind of continuation of, in Putin’s own words, “the thousand-year Russian statehood.” But how did it happen that the revolution that destroyed the Russian Empire, aka the “Prison-house of Nations”, gave rise to a project, certain features of which evoke feelings of nostalgia and revanchism among highly reactionary Russian chauvinists? We publish an excerpt from Marxist historian Vadim Rogovin's book “Stalin's neo-NEP”, in which he describes the transition from the revolutionary deconstruction of the imperial legacy in the early Soviet years to its partial revival in the 1930s. Perhaps it was precisely these changes in the Soviet state that led many to consider it the “same Russia under a different name” and, after its collapse, encouraged the elites of already capitalist Russia to unleash a war to “gather together Russian lands”.

"September" met with mathematician and Russian left-wing politician Mikhail Lobanov to discuss his foreign agent status and his dismissal from the university. We also discussed the potential approaches to anti-war political organizing in Russia and beyond, and learned about Mikhail's plans for the "long-term political mission trip" he embarked on a month ago.

1991, Leningrad. The private office of the deputy mayor of the city. A reporter for the city's television channel interviews a young official from Anatoly Sobchak's team. In the frame — a man with a childish face in a white shirt. Behind him, you can see window blinds, a television, a table lamp, a telephone, open folders with papers. A typical Soviet office environment. But something does not add up. From behind the scenes, the voice of the journalist says that yesterday, he could still see a bust of Lenin in this office, but today it had disappeared somewhere. What had happened?

Ukraine aid, like the war itself, is a point of contention on the international left. Supporters see aid as essential for Ukraine’s defense against an imperialist invader. Skeptics regard it as a giveaway to the war industry at best, a fig leaf for the US empire at worst. The dilemma is that both sides have a point. Aid has enabled Ukraine to push back its occupier, but — funneled through the military-industrial complex of the United States — this success is bound up with both war profiteering and the maintenance of US hegemony. Supporters of aid, among whom I count myself, need to grapple with this ambiguity, which is indicative of the complex issues anti-imperialists will face as great power competition heats up in an increasingly multipolar world.

A recent post about Kyrgyzstan on Instagram by the popular Russian blogger Ilya Varlamov brought a wave of accusations of imperialism upon him. In this critique, the emphasis was on the boorish way the blogger expressed these statements, while the ideological form of Varlamov’s argument, the concept of a ‘service country’ went almost unnoticed. Let us puzzle out what is wrong with this concept and why it gives rise to such ridiculous statements.