Publications for tag «ideology»

How did the ‘democrats’ understand democracy? On the example of the formation of Moscow’s government

Last year, Alexei Navalny initiated a discussion about the role of the 1990s era in the formation of the modern Russian regime. This debate was eagerly supported by the majority of the Russian left, for whom it became an opportunity to remind once again about the undemocratic nature of the formula of democracy as the power of 'democrats'. Nevertheless, questions about the design of the political system of post-Soviet Russia often remain in the background of this discussion. Alexander Zamyatin shows how the political struggle between the "democrats" and the Mossovet on the eve of the first Moscow mayoral elections in 1991 laid the foundations of the system of power in Russia - from plebiscites to the power vertical.

Murad Gattal spoke to Azerbaijani trade unionists and left-wing activists about the state of society following Ilham Aliyev’s election for the fifth presidential term and the Third Karabakh War. The rise of authoritarian tendencies and nationalist rallying around the flag that followed in the aftermath of the ‘small victorious war’ brings up questions about the future, and even existence, of the left movement in the country.

Last August, Alexei Navany published a text, in which he strongly criticised those who, in his opinion, ‘sold, drank, wasted the historic chance which our country had in the early 90s’ - including Boris Yeltsin, ministers of ‘state reform’, and other well-known figures from the post-Soviet Russian elite. This statement, unsurprisingly, led to another round of discussion about the 90s.

A huge scandal in Canadian politics and a painful blow to Ukraine's reputation — these are the terms used by the media to describe how the Canadian parliament and the Ukrainian delegation headed by President Volodymyr Zelenskyy gave a standing ovation to Yaroslav Hunka, a veteran of the Waffen-SS division ‘Galicia’. But how come he was invited to the parliament? Who ‘framed’ Canada and Ukraine? Who gave such a ‘gift’ to Russian propaganda? The Speaker of Parliament, Anthony Rota, took political responsibility for this and resigned. However, it is hard to believe that Mr. Rota knew the SS veteran personally and dreamed of bringing him into the limelight for the whole country to watch. There was someone who came to him with this ‘brilliant’ idea. Let's find out who.

September sat down with Quinn Slobodian, author of Globalists: The End of Empire and the Birth of Neoliberalism and Crack-Up Capitalism: Market Radicals and the Dream of a World Without Democracy to discuss his books, the history of neoliberal and libertarian ideas in the 20th and 21st centuries, the war in Ukraine and the current state of the left-wing movement.

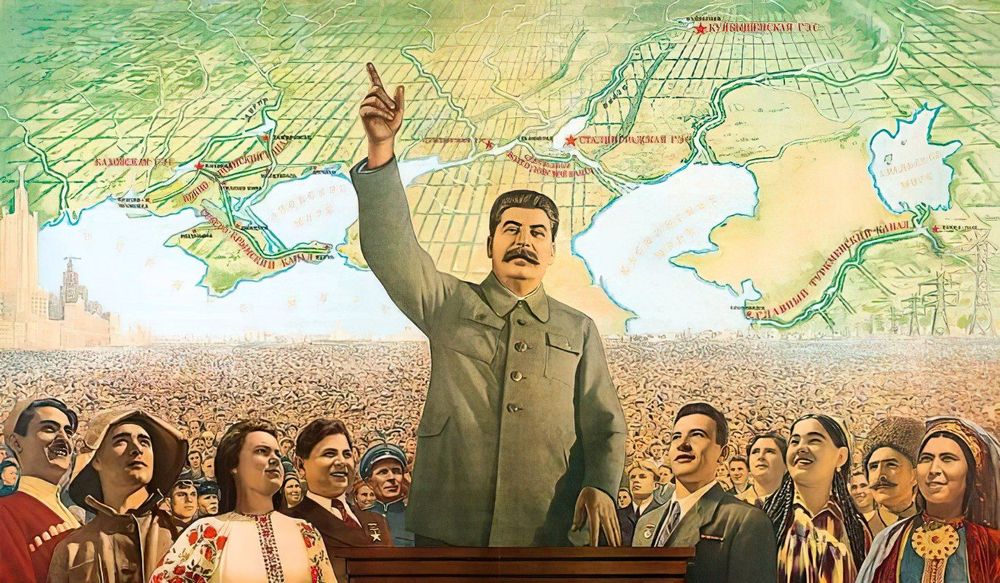

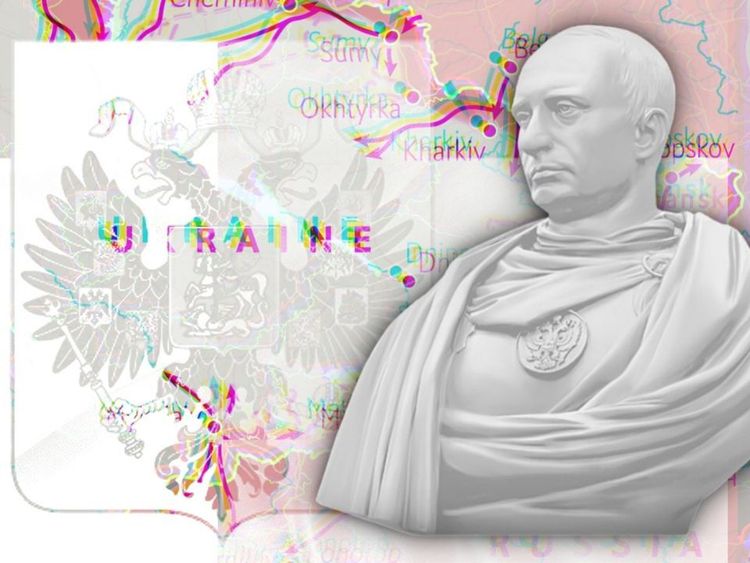

Quite a lot of Russians, including President Vladimir Putin, even though outspoken opponents of the ideas of socialism, nevertheless regard the collapse of the Soviet Union as a personal tragedy. For them, it represented national humiliation for Russia and a chain of major territorial losses. They see in the Soviet project a kind of continuation of, in Putin’s own words, “the thousand-year Russian statehood.” But how did it happen that the revolution that destroyed the Russian Empire, aka the “Prison-house of Nations”, gave rise to a project, certain features of which evoke feelings of nostalgia and revanchism among highly reactionary Russian chauvinists? We publish an excerpt from Marxist historian Vadim Rogovin's book “Stalin's neo-NEP”, in which he describes the transition from the revolutionary deconstruction of the imperial legacy in the early Soviet years to its partial revival in the 1930s. Perhaps it was precisely these changes in the Soviet state that led many to consider it the “same Russia under a different name” and, after its collapse, encouraged the elites of already capitalist Russia to unleash a war to “gather together Russian lands”.

"September" met with mathematician and Russian left-wing politician Mikhail Lobanov to discuss his foreign agent status and his dismissal from the university. We also discussed the potential approaches to anti-war political organizing in Russia and beyond, and learned about Mikhail's plans for the "long-term political mission trip" he embarked on a month ago.

We live in historic times. Historians have long noted that in some periods time seems to thicken, and social contradictions which had previously unfolded gradually are now aggravated and can no longer find room for further coexistence. Current leaders might assure the masses that they are in control of the situation, but if the system goes haywire, this very attempt at mistimed control only worsens the conditions. Gigantic underlying processes are grinding at the superstructural mechanisms, and rulers do not realise the moment that in the long run will make them ex-rulers.

1991, Leningrad. The private office of the deputy mayor of the city. A reporter for the city's television channel interviews a young official from Anatoly Sobchak's team. In the frame — a man with a childish face in a white shirt. Behind him, you can see window blinds, a television, a table lamp, a telephone, open folders with papers. A typical Soviet office environment. But something does not add up. From behind the scenes, the voice of the journalist says that yesterday, he could still see a bust of Lenin in this office, but today it had disappeared somewhere. What had happened?